01/28/2026 Silver, General, General Furniture & Decorative Arts

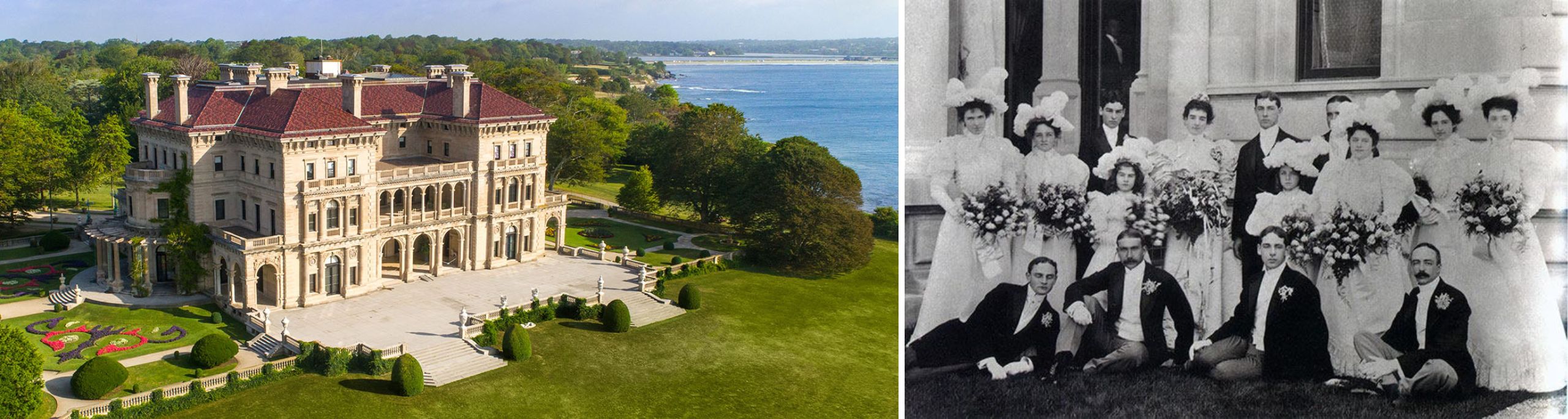

On August 25, 1896, as the summer sun lingered over Newport, Rhode Island, the marriage of Gertrude Vanderbilt and Harry Payne Whitney quietly unfolded within the walls of The Breakers. Though restrained by the standards of America’s most conspicuous families, the wedding nonetheless stood as a defining moment of the Gilded Age—a union that symbolized wealth, power, and the shaping of modern American culture.

At the time, the Vanderbilt name was nearly synonymous with American industrial might. Railroads, steel, and finance had propelled the family into a level of prominence unmatched by most of their contemporaries. Gertrude Vanderbilt, daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, was born into this world of privilege and expectation. Her groom, Harry Payne Whitney, represented an equally formidable lineage: the son of William C. Whitney, former Secretary of the Navy and a towering figure in politics, finance, and sport, and Flora Payne Whitney, heir to a vast Standard Oil fortune. Their marriage united two dynasties whose combined influence reached deep into America’s economic and political life.

Yet this was no ostentatious spectacle like the famously extravagant wedding of Gertrude’s cousin Consuelo Vanderbilt to the Duke of Marlborough just a year earlier. Circumstances dictated restraint. Cornelius Vanderbilt II had suffered a debilitating stroke months before, casting a somber shadow over the family. As a result, the ceremony was intentionally intimate, held not in a large church but in the Music Room of The Breakers, the Vanderbilt summer “cottage” that itself symbolized the era’s excess even when used modestly.

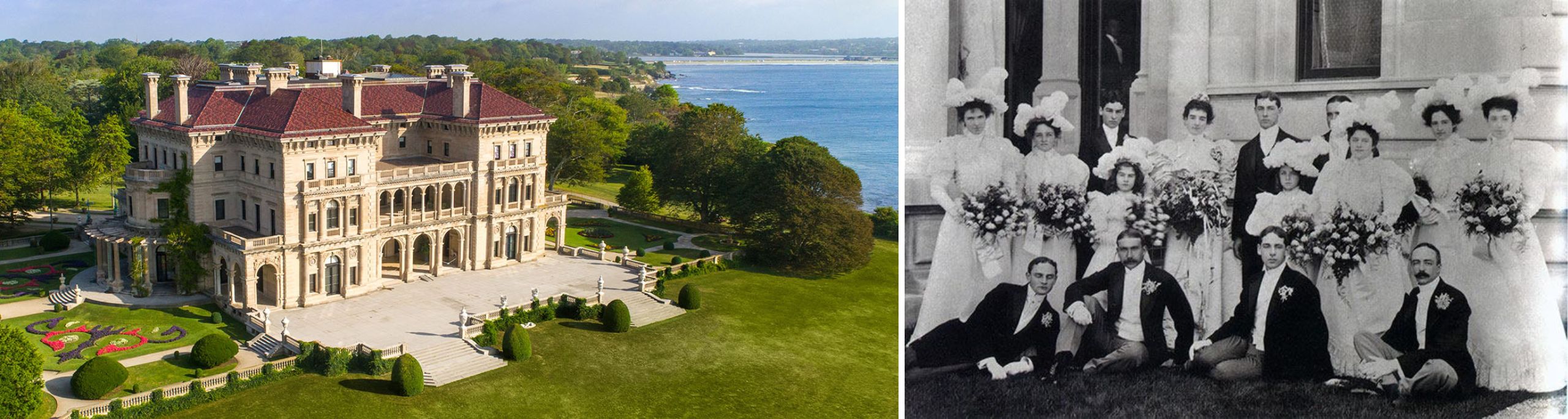

Despite its smaller scale, the wedding reflected refinement rather than restraint. According to contemporary accounts from The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Gertrude’s bridal gown was a vision of heritage and elegance: white satin trimmed with old lace that had been treasured by the family for generations. She wore her mother’s bridal veil, linking past and present in a gesture that underscored dynastic continuity. Her bouquet of stephanotis and gardenia conveyed both purity and understated luxury. The bridesmaids, dressed in mousseline de soie over white silk with Valenciennes lace and rose-colored belts, added soft color and movement to the scene, embodying the genteel fashion of the 1890s.

The bridal party itself read like a social register of America’s elite. Gertrude was attended by her sister Gladys Vanderbilt and by Dorothy Whitney, sister of the groom, while Alfred Vanderbilt, Gertrude’s brother, served as an usher. Even the legal nuances of the ceremony reflected the complexities of the era: though the marriage was legally solemnized by the Reverend George F. Magill of Trinity Church in New York, Rhode Island law prohibited an out-of-state clergyman from officiating. Thus, the Newport ceremony became ritualistic, with Bishop Potter presiding—an elegant workaround befitting families accustomed to navigating power and protocol.

The significance of this marriage extended far beyond the wedding day. Lavish gifts poured in, including a townhouse from William C. Whitney, as well as important silver (see lots 102, 103, 104 below), affirming the union’s material splendor. More importantly, the marriage set the stage for Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s transformation into one of the most influential cultural figures of the twentieth century. Though born into wealth, Gertrude would not be content merely to inherit privilege. She became a pioneering sculptor and an extraordinary patron of the arts, eventually founding what is now the Whitney Museum of American Art. In this sense, the wedding marked not just the joining of two families, but the beginning of a legacy that helped redefine American artistic identity.

In retrospect, the Whitney-Vanderbilt wedding stands as a quiet yet powerful emblem of its time. It captured the tension of the Gilded Age: immense wealth tempered by personal vulnerability, grandeur softened by circumstance, and private moments unfolding against the backdrop of national transformation. While the ceremony itself may have been modest by Vanderbilt standards, its historical resonance endures. In uniting Gertrude Vanderbilt and Harry Payne Whitney, the event helped shape not only America’s social elite, but also its cultural future—proof that even the most intimate moments can leave an indelible mark on history.

Auction Wednesday, February 11, 2026 at 10am

Exhibition February 5 – 9

Sale Info

Featured in the auction are elegant wedding gifts presented to Gertrude Vanderbilt by members of the Vanderbilt family – a sterling silver tea and coffee service from her grandmother Maria Louisa Kissam Vanderbilt (Lot 104) and a sterling silver pair of candelabra and four matching candlesticks from her aunt Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard (Lot 103, Lot 102).